Ouo.io

Ouo.io is one of the fastest growing URL Shortener Service. Its pretty domain name is helpful in generating more clicks than other URL Shortener Services, and so you get a good opportunity for earning more money out of your shortened link. Ouo.io comes with several advanced features as well as customization options.

With Ouo.io you can earn up to $8 per 1000 views. It also counts multiple views from same IP or person. With Ouo.io is becomes easy to earn money using its URL Shortener Service. The minimum payout is $5. Your earnings are automatically credited to your PayPal or Payoneer account on 1st or 15th of the month.- Payout for every 1000 views-$5

- Minimum payout-$5

- Referral commission-20%

- Payout time-1st and 15th date of the month

- Payout options-PayPal and Payza

Clk.sh

Clk.sh is a newly launched trusted link shortener network, it is a sister site of shrinkearn.com. I like ClkSh because it accepts multiple views from same visitors. If any one searching for Top and best url shortener service then i recommend this url shortener to our users. Clk.sh accepts advertisers and publishers from all over the world. It offers an opportunity to all its publishers to earn money and advertisers will get their targeted audience for cheapest rate. While writing ClkSh was offering up to $8 per 1000 visits and its minimum cpm rate is $1.4. Like Shrinkearn, Shorte.st url shorteners Clk.sh also offers some best features to all its users, including Good customer support, multiple views counting, decent cpm rates, good referral rate, multiple tools, quick payments etc. ClkSh offers 30% referral commission to its publishers. It uses 6 payment methods to all its users.- Payout for 1000 Views: Upto $8

- Minimum Withdrawal: $5

- Referral Commission: 30%

- Payment Methods: PayPal, Payza, Skrill etc.

- Payment Time: Daily

Adf.ly

Adf.ly is the oldest and one of the most trusted URL Shortener Service for making money by shrinking your links. Adf.ly provides you an opportunity to earn up to $5 per 1000 views. However, the earnings depend upon the demographics of users who go on to click the shortened link by Adf.ly.

It offers a very comprehensive reporting system for tracking the performance of your each shortened URL. The minimum payout is kept low, and it is $5. It pays on 10th of every month. You can receive your earnings via PayPal, Payza, or AlertPay. Adf.ly also runs a referral program wherein you can earn a flat 20% commission for each referral for a lifetime.Short.am

Short.am provides a big opportunity for earning money by shortening links. It is a rapidly growing URL Shortening Service. You simply need to sign up and start shrinking links. You can share the shortened links across the web, on your webpage, Twitter, Facebook, and more. Short.am provides detailed statistics and easy-to-use API.

It even provides add-ons and plugins so that you can monetize your WordPress site. The minimum payout is $5 before you will be paid. It pays users via PayPal or Payoneer. It has the best market payout rates, offering unparalleled revenue. Short.am also run a referral program wherein you can earn 20% extra commission for life.LINK.TL

LINK.TL is one of the best and highest URL shortener website.It pays up to $16 for every 1000 views.You just have to sign up for free.You can earn by shortening your long URL into short and you can paste that URL into your website, blogs or social media networking sites, like facebook, twitter, and google plus etc.

One of the best thing about this site is its referral system.They offer 10% referral commission.You can withdraw your amount when it reaches $5.- Payout for 1000 views-$16

- Minimum payout-$5

- Referral commission-10%

- Payout methods-Paypal, Payza, and Skrill

- Payment time-daily basis

CPMlink

CPMlink is one of the most legit URL shortener sites.You can sign up for free.It works like other shortener sites.You just have to shorten your link and paste that link into the internet.When someone will click on your link.

You will get some amount of that click.It pays around $5 for every 1000 views.They offer 10% commission as the referral program.You can withdraw your amount when it reaches $5.The payment is then sent to your PayPal, Payza or Skrill account daily after requesting it.- The payout for 1000 views-$5

- Minimum payout-$5

- Referral commission-10%

- Payment methods-Paypal, Payza, and Skrill

- Payment time-daily

Linkbucks

Linkbucks is another best and one of the most popular sites for shortening URLs and earning money. It boasts of high Google Page Rank as well as very high Alexa rankings. Linkbucks is paying $0.5 to $7 per 1000 views, and it depends on country to country.

The minimum payout is $10, and payment method is PayPal. It also provides the opportunity of referral earnings wherein you can earn 20% commission for a lifetime. Linkbucks runs advertising programs as well.- The payout for 1000 views-$3-9

- Minimum payout-$10

- Referral commission-20%

- Payment options-PayPal,Payza,and Payoneer

- Payment-on the daily basis

Concrete recycling is an increasingly common method of recycling unwanted concrete that normally is trucked to landfills for disposal. The concrete industry culture prevents the process from going full circle. We recycle demolished or renovated concrete structures, utilizing the rubble as the dry aggregate for brand new concrete. Taking the recycling process full cycle drastically lowers costs by allowing flexibility with scheduling, and lowering material cost.

Friday, March 29, 2019

7 Best Highest Paying URL Shortener Sites to Make Money Online 2019

THE EISENKERN GRAV-STUG KICKSTARTER IS NOW LIVE!

RPGs As Emotional Gambling

When you make a PC, you're investing a little bit of creativity into them. You put some time and thought into who they are and what they want. Creativity is, to my mind, quite personal; sharing the fruits of your creativity with others is exposing a little bit of your inner self to them (this, incidentally, is at the heart of the issues I have with many 'pass the talking-stick' story-games). The more you play the PC, the more you invest in them emotionally. The more of an emotional stake you have in them surviving and prospering.

When a PC dies (or is otherwise irretrievably fucked up), all that emotional energy you'd tied to them is lost with them. It's a sudden gut-punch of loss. The risk of that upset is what makes the game exciting. IC successes (gaining magic items, levelling up, increasing IC status) feel good because we know that they make the gut-punch of character death less likely; IC setbacks feel a bit bad for the same reason.

Things that drag the loss out (such as being temporarily turned into a frog, knocked unconcious or otherwise rendered unplayable) feel worse than mere death, because after a PC dies you can quickly recover, make a new PC and get back into the swing of things. An extended time where your PC is useless means you're stuck in that low-point for longer, hoping to get the PC you've invested in back soon.

Having agency over how a character's arc ends has been, in my experience, important. Retiring a PC who's become difficult to play (due to curses, injuries, etc etc) feels better than having them die, because the player gets to choose it, and can imagine them sitting in a nice cottage somewhere, with a big pile of gold, a sword hung over the fire-place, and a small child on their knee that they're telling the story of 'how I got my eye torn out'. It's a Good Ending. In effect, you're cashing out your 'emotional chips', and calling this gamble a success.

For this emotional gamble to be worth it, you need to carefully balance the emotions invested in the PC, the likelihood of death, and the magnitude of the gut-punch when the PC does die. I think the OSR gets this right with it's lower investment into new PC - rolling up a character is quick and doesn't require much deep thought, and low level PCs are fragile as fuck - that allows greater investment over time, corresponding to greater survival chances. Compare this to modern D&D where character creation takes ages (resulting in high investment from the get-go), CR-balanced encounters mean that your chance of death is constant rather than scaling to reflect investment, and death is rare enough that its easy to disregard entirely; here, your investment-risk-gutpunch balance is all off, you invest highly in a PC but have little tension, there's no sense of safety from levelling up since the challenges get harder to match you, and when you DO die it feels arbitrary, unexpected and unusually horrid (which feeds back into GMs not being willing to kill PCs, resulting in EVEN LESS tension).

One thing which I do in my games is to include horrible wounds. These actually tend to result in slightly longer gut-punches, as playing a PC missing a bunch of body parts is kind of difficult, and bleeding out extends the process of dying. However, they also soften the gut-punch as you're more likely to be able to successfully retire a (now crippled but also very wealthy) PC, getting them a good ending.

I tend to avoid anything which temporarily makes a PC unplayable (such as hard mind-control, extended unconciousness, transformation, etc), since this keeps the gut-punch just as horrid but draaaags it out. Instead, these effects tend to be either permanent (effectively character death) or just a debuff that encourages you retire the character.

Going To Rapier Con Febuary 8-10

My son and I will be going to Rapier Con in Jacksonville, FL during the weekend of February 8-10. It's the first time I'll have played real miniature games in years. We're looking forward to it. Plus, I got a new cell phone (S9+) over the holidays, so I actually have an awesome camera again to shoot photos. It's been years since I had a good camera, hence the lack of photos and articles here. I'm edging my way back into miniature gaming. :-)

My son and I will be going to Rapier Con in Jacksonville, FL during the weekend of February 8-10. It's the first time I'll have played real miniature games in years. We're looking forward to it. Plus, I got a new cell phone (S9+) over the holidays, so I actually have an awesome camera again to shoot photos. It's been years since I had a good camera, hence the lack of photos and articles here. I'm edging my way back into miniature gaming. :-)Thursday, March 28, 2019

Storium Theory: Optional Challenges

Most of the time, when we put down a challenge, it's definite - a note that the story will be focusing on a particular point. But is it possible to use challenges differently? To lay down a challenge for something the players might want to focus on, but are not required to focus on?

But should you decide to use this tool, I think there are some very important things you will need to be sure you address.

I believe it is a tool for the toolbox...but one I would show great caution in using. I've only pulled out an optional challenge once or twice in my own games, and I am wary of using them often, if at all, in my own narration generally. Storium's rules are set up more for completion of challenges and requiring of challenges, and I think there's a good reason for that.

In setup, an optional challenge wouldn't be so different from a regular challenge - you still want to establish the starting situation, the facts of the challenge, and the possible places the challenge can end up once it is complete. There's not much different in the overall technique of setting it up.

But should you decide to use this tool, I think there are some very important things you will need to be sure you address.

First: How will you know if players are or are not going to play on the challenge? You will need a good way of knowing if players have not played on a challenge yet because they haven't gotten to it yet, or because they do not intend to play on it at all. An optional challenge, being optional, could be ignored completely by players for reasons that have nothing to do with slow play or inactivity. It is important to have a way of determining that the players are not going to play on the challenge, and that it is time to move the scene on.

I suggest that you consider one of the following ideas:

- Set a deadline based on the other challenges - if the optional challenge is not completed by the time the scene's other challenges are, you will consider it incomplete and move the scene on.

- Set a deadline based on actual time - if the optional challenge is not completed within X days after the rest of the scene's challenges are (or just within X days if there are no other challenges) you will consider it incomplete and move the scene on.

- Require an affirmative statement from a player that they intend to play on the optional challenge by a specific date. If you have no such statement by that date, you will remove the optional challenge.

These methods are probably not the only ones...or even likely the best...but they all allow you to know when you can regard the challenge as incomplete and move forward. Whatever choice you make, be sure you tell your players so they know what the requirements are.

Second: What happens when the optional challenge is incomplete?

This is a pretty important question, and one that, I think, gets at the reason I don't use optional challenges much. If something's critical enough to the story that you want to set up a challenge for it, it seems like it is something the group should have to interact with - even if their interaction is playing Weakness cards and having their characters utterly ignore it and let it go wrong. In other words, the characters might not care about something, but if it is important enough to the story to rate a challenge, the players should have to do something about it...even if that something is having their characters do nothing. The story of the challenge, once laid out, should probably progress.

If it goes well, then, it ends Strong. If it goes poorly, it ends Weak. If it is less clear, it ends Uncertain. But that's all determined by the cards.

So...what do you do with a challenge that seemed interesting enough to put out there as an option, but that seems like something the character's don't have to address?

My best bet is that you do nothing. An optional challenge is something that is interesting, but not critical. The players don't gain or lose anything by not going after it. It's only if they actually engage it that it matters to the story in any way.

Thus, if the players don't seem interested in it and leave it alone, it just drops off for the moment. Nothing bad happens, nothing good happens. It just fades away into the background again.

That's not to say you can't bring it back again later, or bring it back again later as a normal, required challenge. It's just that for the moment, it wasn't critical enough to be made required, so nothing's reaching any kind of story-altering point with it. It just fades away for now.

If on the other hand players play some of the cards on the challenge, but don't finish it, I'd probably go by my usual rule for ending a challenge early when it becomes absolutely necessary: Most likely, end it by whatever the current result would be (i.e. if it is going Strong, it ends Strong, if it is going Weak, it ends Weak, if it is going Uncertain, it ends Uncertain) - this method makes the players' card plays so far clearly matter, so that's my preference. If you use a different rule for those cases in your own games, be consistent.

But that brings me to another consideration...

Third: How many points do you put on the thing, anyway?

I'm going to just say outright that I think the answer is one, possibly two at maximum. An optional challenge is not the focus of the scene - it is by definition something that can be entirely ignored. Thus, it isn't anywhere near as important as other challenges, and shouldn't get a lot of focus in the scene at hand.

Furthermore, if you put more points on an optional challenge, it makes it harder to judge when players no longer care about it - once it has become active, how do you judge that it isn't going to be active any further? You can always rule that an optional challenge becomes required if at least one player plays a card on it, of course, but that could get messy in terms of game morale and community if players disagree about whether they want to play on it.

So...I suggest making your life as easy as possible by using only one or two points, tops, and making clear to your players that whatever "deadline" you set for the optional challenge is a completion deadline, not a play deadline - the challenge needs to be complete by then or you will move things on. That will prevent an optional challenge from causing delays.

Finally, though: Consider whether the challenge should even be optional in the first place.

Most of the things I've considered as, well, optionally "optional" challenges were ideas that I ended up deciding would either fit perfectly well as required challenges right then, or would fit perfectly well as required challenges later. I've rarely come across something that I considered important to note in challenge form, but not critical enough to be something the players had to address.

If you're considering an optional challenge, think about it a bit more for a while...is it really something that should be optional, or is it just something that hasn't come to a head yet? Maybe it's something you can get some actual drama out of later, and make it a normal challenge in a later scene. Or maybe it's something you can hint at with a minor required challenge now - perhaps to see if someone notices something - and bring in more fully down the line.

Or perhaps it is something that actually is pretty vitally important right now, in which case it should be a required challenge...right now.

So, when can an optional challenge be helpful?

I could see them being useful if you want to allow the group to choose a direction, but neither direction is necessarily better or worse for the story (if one direction is better and the other is worse, you'd instead do a regular challenge and set the first up as the Strong outcome and the second as the Weak). Then, you could set up two different one-point challenges, and tell the players they can only do one of them - that sets them off on that path and determines how it starts out for them.

It isn't my chosen way to find where the players want to go in the story, but I could see it working.

Another method might be something that is solidly an opportunity for the players - again, if they don't do anything, it doesn't go wrong or anything like that, but perhaps it is something they can use to "shortcut" the plot in some way. You'd have to be careful with this one - it's easy to run into the "why don't you just do this as a regular challenge" internal question - but there are ways I could see it working. If you do this, then, the Strong result is very good for the characters, and the Weak result is perhaps less so, but still generally quite good.

The problem I run into myself with that is that if you use that method, it becomes hard to argue that things aren't worse if the player decide not to play the challenge...in which case, again, I feel like it probably shouldn't be optional because it impacts the story in a notable way. And that's exactly where I've ended up when I've reflected on the few times I've used optional challenges...I end up feeling like what I did was render a part of the story optional when it was actually going to have a definite impact.

And that's the point I keep coming back to myself in considering this - I just generally can't justify putting a challenge down and treating it as "optional." When I put a challenge down, it means that a notable event has started in the story, and the players, through their card plays, need to see where it goes. It needs to get to some conclusion or another, so that we know where the story goes after it. When I find myself thinking of perhaps telling my players a challenge is optional, I start instead thinking of whether it should be there yet at all.

But: I know that this is a technique some other narrators have used in the past, and I'd very much be interested to hear others' thoughts on it. Have you used optional challenges? What did they represent in your game? And how did you ensure that you knew it was fine to move the game forward? Write in, and let me know!

Game 321: Star Control II: The Ur-Quan Masters (1992)

|

| Let's not judge this one by its title screen . . . |

Star Control II: The Ur-Quan Masters

United States

Toys for Bob (developer); Accolade (publisher)

Released in 1992 for DOS, 1994 for the 3DO console; later fan ports to other platforms

Date Started: 23 March 2019

When I started this blog in 2010, I had already played, at least in adolescence--most of the RPGs that everyone else knows. I may not have remembered all of the details, but I at least could remember the basic outlines of The Bard's Tale, Might and Magic, Wizardry, Questron, Pool of Radiance, and all of the Ultimas. There were lots of games I had never played--never even heard of--of course, but those were games that most other people my age had never encountered either. It wasn't until about a year into my blog, with Dungeon Master, that I truly felt I was blogging about a game that I should be ashamed for never having played previously.

For the first time since then, I am in that position again with Star Control II, a game that frequently makes "top X" lists of the best games of all time. My commenters have mentioned it so many times that my usual pre-game search of previous comments turned up too many results to analyze. This one, in other words, is really going to fill a gap.

|

| . . . even though the first game had an awesome title screen. |

There has been some debate about whether Star Control II is an RPG, but at least almost everyone agrees that its predecessor was not. That predecessor went by the grandiose name Star Control: Famous Battles of the Ur-Quan Conflict, Volume IV (1990), in an obvious homage to Star Wars. It's an ambitious undertaking--part simulator, part strategy game, part action game. The player has to manage ships and other resources and plan conquests of battle maps, but in the end the conflict always comes down to a shooting match between two ships using Newtonian physics and relying almost entirely on the player's own dexterity. This combat system goes back to Spacewar! (1962) and would be familiar to anyone who's played Asteroids (1979).

The setup has an Earth united under one government by 2025. In 2612, Earth is contacted by a crystalline race called the Chenjesu and warned that the Ur-Quan Hierarchy, a race of slavers, is taking over the galaxy. (Star Control II retcons this date to 2112.) Earth is soon enlisted into the Alliance of Free Stars and agrees to pool resources in a mutual defense pact. The Alliance includes Earth, the philosophic Chenjesu, the arboreal Yehat, the robotic Mmrnmhrm, the elfin Ariloulaleelay, and a race of all-female nymphomaniacs called the Syreen who fly phallic ships with ribbed shafts.

On the other side are the Ur-Quan, an ancient tentacled species with a strict caste system. They make slaves out of "lesser races" and only communicate with them via frog-like "talking pets." Their allies include Mycons, a fungus species; Ilwraths, a spider-like race that never takes prisoners; and Androsynths, disgruntled clones who fled captivity and experimentation on Earth. Each race (on both sides) has unique ship designs with various strengths and weaknesses, some of which nullify other ships. There's a kind-of rock-paper-scissors element to strategically choosing what ships you want to employ against what enemies.

|

| No "bumpy forehead" aliens in this setting. |

The occasionally-goofy backstory and description of races seems to owe a lot (in tone, if not specifics) to Starflight (1986), on which Star Control author Paul Reiche III had a minor credit. There are probably more references than I'm picking up (being not much of a sci-fi fan) in the ships themselves. "Earthling Cruisers" (at least the front halves) look like they would raise no eyebrows on Star Trek, and both Ilwrath Avengers (in the back) and Vux Intruders (in the front) look like Klingon warbirds. The Ur-Quan dreadnought looks passably like the Battlestar Galactica.

The original Star Control offers the ability to fight player vs. player or set one of the two sides to computer control (at three difficulty levels). In playing, you can simply practice ship vs. ship combat with any two ships, play a "melee" game between fleets of ships, or play a full campaign, which proceeds through a variety of strategic and tactical scenarios involving ships from different species in different predicaments. The full game gives player the ability to build colonies and fortifications, mine planets, and destroy enemy installations in between ship-to-ship combats.

|

| The various campaign scenarios in the original game. |

The "campaign map" in the original game is an innovative "rotating starfield" that attempts to offer a 3-D environment on a 2-D screen. It takes some getting used to. Until they reach each other for close-quarters combat, ships can only move by progressing through a series of jump points between stars, and it was a long time before I could interpret the starfield properly and understand how to plot a route to the enemy.

|

| Strategic gameplay takes place on a rotating starmap meant to simulate a 3-D universe. |

I have not, in contrast, managed to get any good at ship combat despite several hours of practice. I'm simply not any good at action games. At the same time, I admire the physics and logistics of it. You maintain speed in the last direction you thrust even if you turn. You have limited fuel, so you can't go crazy with thrusting in different directions. You can get hit by asteroids, or fouled in the gravity wells of planets. And you have to be conservative in the deployment of your ships' special abilities, because they use a lot of fuel. Still, no game in which action is the primary determiner of success is going to last long on my play list. For such players, the game and its sequel offer "cyborg" mode, where technically you're the player but the computer fights your battles, but I'd rather lose than stoop to that.

|

| One of my lame attempts at space combat. |

Star Control II opens with a more personal backstory. In the midst of the original Ur-Quan conflicts, the Earth cruiser Tobermoon, skippered by Captain Burton, was damaged in an ambush and managed to make it to a planet orbiting the dwarf star Vela. As they tried to repair the ship, crewmembers found a vast, abandoned underground city, populated with advanced technology, built by an extinct race known as the Precursors.

|

| The backstory is reasonably well-told with title cards. |

Burton reported the find when she returned to Earth, and she was ordered to return with a scientific team led by Jules Farnsworth. Shortly after they arrived, they received word from Earth that the Ur-Quan had learned about the Precursor city and were on their way. Burton balked at Earth's orders to abandon and destroy the base with nuclear weapons. Instead, she sent her ship back to Earth under the command of her first officer and remained behind with the scientific team, planning to detonate nuclear weapons should the Ur-Quan ever arrive.

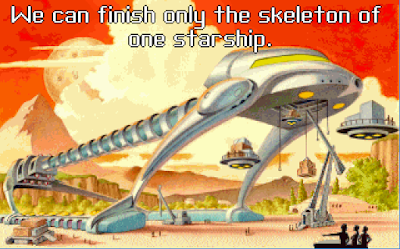

The team ended up spending 20 years on the planet, which they named Unzervalt, with no contact from Earth. During that time, the scientists discovered that the city had been created to build ships, and eventually they were able to activate the machines, which put together a starship. The machines shut down just as the ship was completed, reporting that there were insufficient raw materials to continue. About this time, Farnsworth admitted that he was a fraud, and all the success he'd experienced getting the machines up and running was due to a young prodigy born on Unzervalt--the player character.

|

| They're not kidding about the "skeleton" part. |

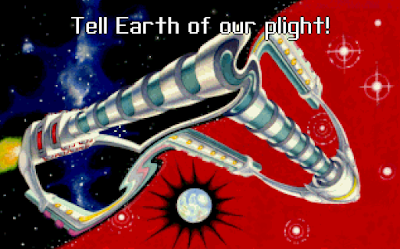

Burton assembled a skeleton crew for the new starship, with the PC manning the computer station, and blasted off. Three days out, they discovered the derelict Tobermoon, damaged and bereft of any (living or dead) crewmembers. Burton took command of the Tobermoon while the PC was promoted to captain of the new ship. Tobermoon was soon attacked and destroyed by an unknown alien craft, leaving the new ship to escape to Earth. Here the game begins.

|

| What "plight"? You live on a technologically-advanced Eden where your enemies seem to have forgotten about you. |

The player can name himself and his ship, and that's it for "character creation." He begins in the middle of the solar system, in a relatively empty ship with 50 crew and 10 fuel. I intuited that I needed to fly towards Earth, so I headed for the inner cluster of planets.

|

| "Character creation." |

As the screen changed to show Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, a probe zoomed out and attached itself to our ship. It played a recording from an Ur-Quan (with the "talking pet" doing the talking), informing me that approaching Earth was forbidden, as was my status as an "independent" vessel. The probe then zoomed off to inform the Ur-Quan of my "transgressions," leaving me to explore the planetary area at will. I guess the war didn't go so well for the Alliance.

|

| Well, we now know how the first game ended, canonically. |

As I approached Earth, the screen changed to show Earth, the moon, and a space station orbiting Earth. Earth itself seemed to have some kind of red force field around it, so I approached the space station.

As I neared, I was contacted by a "Starbase Commander Hayes of the slave planet Earth." He indicated that his energy cores were almost depleted and asked if we were the "Hierarchy resupply ship." At this point, I had a few dialogue options. One allowed me to lie and say I was the resupply ship. Another had me introduce myself. A third--more reflective of what I was actually thinking--said "'Slave planet?!' 'Hierarchy resupply vessel?!' What is going on here?'" The commander said he'd answer my questions if we'd bring back some radioactive elements to re-power the station. He suggested that we look on Mercury.

|

| I like dialogue options, but so far they've broken down into: 1) the straight, obvious option; 2) the kind-of dumb lie; and 3) the emotional option that still basically recapitulates #1. |

I flew off the Earth screen and back to the main solar system screen. At some point during this process, I had to delete the version of the game that I'd downloaded and get a new one. None of the controls worked right on the first one I tried. I particularly couldn't seem to escape out of sub-menus, which was supposed to happen with the SPACE bar. The second version I downloaded had controls that worked right plus someone had removed the copy protection (which has you identifying planets by coordinates). The controls overall are okay. They're much like Starflight, where you arrow through commands and then hit ENTER to select one. I'd rather be able to just hit a keyboard option for each menu command, but there aren't so many commands that it bothers me. Flying the ship is easy enough with the numberpad: 4 and 6 to turn, 8 to thrust, 5 to fire, ENTER to use a special weapon. There's a utility you can use to remap the combat commands, but using it seems to run the risk of breaking the main interface, which I guess is what happened with the first version I downloaded.

|

| Running around Mercury and picking up minerals. The large-scale rover window (lower right) is quite small. |

When orbiting a planet, you get a set of options much like Starflight. You can scan it for minerals, energy, or lifeforms, and then send down a rover (with its own weapons and fuel supply) to pick things up. Minerals are color-coded by type, and at first I was a little annoyed because I can't distinguish a lot of the colors. But it turns out that the explorable area of planets is quite small, and you can easily zoom around and pick up all minerals in just a few minutes. In that, it's quite a bit less satisfying than Starflight, where the planets were enormous and you'd never explore or strip them all, and you got excited with every little collection of mineral symbols.

The rover doesn't hold much, but returning to the ship and then landing again is an easy process, so before long my hold was full of not just uranium and other "radioactives," but iron, nickel, and other metals. In mining them, the rover was periodically damaged by gouts of flame from the volatile planet, but it gets repaired when you return to the main ship.

|

| Returning to base with a near-full cargo manifest. |

We returned to the starbase and transferred the needed elements. With the station's life support, communications, and sensors working again, the captain was able to scan my vessel, and he expressed shock at its configuration. Rather than give him the story right away, I chose dialogue options that interrogated him first.

|

| This seems to be everybody's reaction. |

Commander Hayes explained that the Ur-Quan had defeated the Alliance 20 years ago. They offered humanity a choice between active serve as "battle thralls" or imprisonment on their own planet. Humanity chose the second option, so the Hierarchy put a force field around the planet, trapping the human race on a single world and preventing assistance from reaching them. But they also put a station in orbit so their own ships could find rest and resupply if they happened to pass through the system. The station is maintained by humans conscripted from the planet for several years at a time.

|

| Humanity's fate didn't seem so bad until he got to this part. |

When he was done, I (having no other choice, really) gave him our background and history and asked for his help. Pointing out that starting a rebellion and failing would result in "gruesome retribution," he asked me to prove my efficacy by at least destroying the Ur-Quan installation on the moon, warning me that I would have to defeat numerous warships.

We left the station and sailed over to the moon. An energy scan showed one blaze of power, so I sent the rover down to it. The report from the rover crew said that the alien base was abandoned and broadcasting some kind of mayday signal, "but great care has been taken to make it appear active." My crew shut the place down and looted it for parts.

|

| My crew files a "report from the surface." |

Lifeform scans showed all kinds of dots roaming around the moon, most looking like little tanks. I don't know if I was supposed to do this or not, but I ran around in the rover blasting them away in case they were enemies. I also gathered up all the minerals that I could.

I returned to the starbase, and the commander accepted my report. Just then, an Ilwrath Avenger, having found the probe, entered the system. The arachnid commander threatened us. There were some dialogue options with him, all of which I'm sure resulted in the same outcome: ship-to-ship combat.

|

| They're not just "spider-like"; they actually spin webs on their bridges. |

This part was much like the original game, although with the ship icons larger and against a smaller backdrop. I (predictably) lost the battle the first two times that I tried, but won the third time. In my defense, the game's backstory specifically said that I had minimal weapons. It was also a bit lumbering--slow to turn, slow to thrust.

|

| The alien ship destroys me in our first encounter. |

When I returned to starbase after the battle, Commander Hayes said he would join my rebellion, and the starbase would be my home base. He asked what we would call our movement, and there were some amusing options.

|

| The last option tempted me, but I was boring and went with the first one. |

Through a long series of dialogues, I learned that as I brought back minerals and salvage, the base could convert them into "resource units" (RU) which I could then use to build my crew, purchase upgrades for the Prydwen (improved thrusters, more crew pods, more storage bays, more fuel), get refueled, and build a fleet of starships. I can even build alien ships if I can find alien allies to pilot them.

|

| My own starbase. Why can't I name it? |

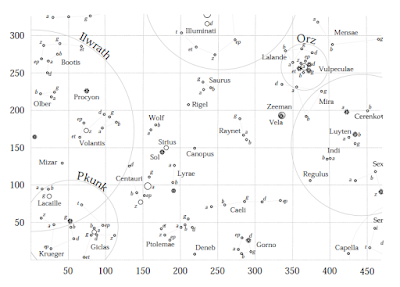

Hayes had a lot more dialogue options related to history and alien species, but I'll save those for later. It appears that the introduction is over and I now have a large, open universe to explore, where I'm sure I'll do a lot of mining, fighting, and diplomacy. In this sense, Star Control II feels like more of a sequel to Starflight than the original Star Control.

|

| One part of a nine-page starmap that came with the game. I'm tempted to print it out and assemble it on the wall in front of my desk. I suppose it depends on how long the game lasts. |

I appreciate how the game eased me into its various mechanics. I'm enjoying it so far, and I really look forward to plotting my next moves. I suspect I'll be conservative and mine the rest of the resources in the solar system and buy some modest ship upgrades before heading out into the greater universe.

Time so far: 2 hours

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)